Labwork – my latest discovery

November 7, 2014

This month’s topic will reveal a professional insecurity which I have. Up to now I have been a field ecologist. Think hiking boots and hand-lens rather than white coat and goggles. Working with life–sized systems in a real landscape brings with it a great deal of unpredictability and complication as well as budgetary and time challenges; weather, livestock and human interference can confound the best laid plans. Fundamentally, most vegetation data recording comes down to a person in a field with a clipboard deciding what percentage of the space is occupied by each plant species they record. We do our best, but it is a bit approximate even in optimal conditions. On a cold windy day? Let’s just say decisions tend to be made quickly. Knowing all of this has removed the mystery from my job and made me feel that the day to day work of a field ecologist is, well, not very scientific.

Over the last month, however, all this has changed. I have been sampling water and carrying out analyses in a laboratory. Roll on the white coat and goggles.

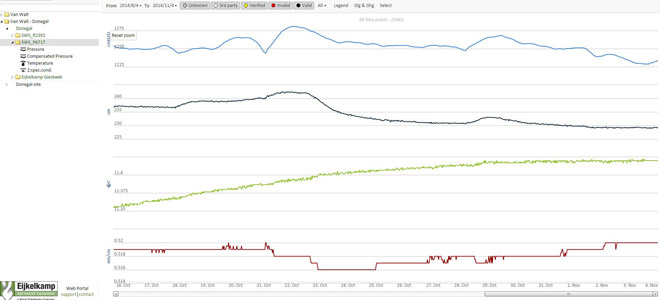

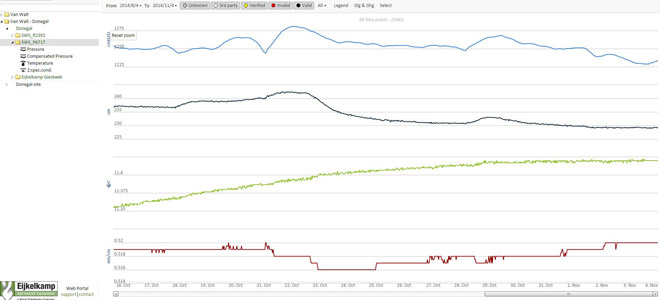

At the start of this month I took water samples from all of my wells in county Donegal. This was not without challenges as there was a lot of rinsing and filtering and carrying heavy expensive equipment over fields to my wells, thinking all the time about how fast I could get my samples back to Dublin for time sensitive analysis. In the end it took two trips and involved some hair tearing moments as equipment failed, batteries ran out and light left the skies, but eventually all the samples made it back to the lab.

As this was the first sampling run, we really did not know what to expect from the samples. The best thing to do was to be as thorough as possible so that we could get a good picture of the nutrient status, calcium carbonate content and dissolved ions present in the water.

So what are the biggest revelations of this phase of my project?

2: What really matters as a scientist is whether you can record data with enough precision to detect changes or find patterns in a system. A visual appraisal of the cover of different plants might not seem as scientific as an exact 5ml dose of reagent in a test tube, but it has been proven to work in practice. All that is missing is the (somewhat dubious) glamour of the laboratory.

3: Whereas it often doesn’t matter whether there is a difference of 1% in the cover of a plant you record in vegetation science, small mistakes can make a huge difference in water analysis. Even a tiny amount of contaminant left on a test tube from previous use can double the amount of phosphate you record in your sample. This is particularly true if you are working in relatively untouched, unpolluted waters.

4: It appears that I am working in relatively untouched, unpolluted waters. I will have to be very careful indeed in my collection and analysis of water samples. The levels of phosphate and nitrate that I am recording at most sites are very low in comparison to similar habitats elsewhere. The next step for my research will be to find out what levels are of ecological significance.

6: Pieces of equipment in the lab can have surprisingly evocative names. The spectrophotometer should appear in a Victorian gothic novel, but instead it tells me how much phosphate is present in my water samples. The sonicator – not a Dr Who prop, but a bath which helps substances to dissolve in liquid or removes dissolved gasses. Perhaps my favourite is the vortex mixer which mixes the ingredients in a test tube by producing a thimble-sized whirlpool.

If I am honest, I thought I would find lab work dull and restrictive, but the opposite is true. Finding out more about my sites is always satisfying, and I am keenly aware of the advantages of being able to work in a controlled environment. I have done just enough chemistry to understand the principles which underlie the methods I am using, but taking a colourless sample of water, adding several other clear ingredients and watching the test tube turn blue still gives me a thrill. And yes, in my lab coat and goggles, I do feel more like a real scientist!

Aoife Delaney

You might also be interested in...

Van Walt Guidelines for sampling for PFAS in Groundwater

November 13, 2024We need to make clear, that at the time of writing, there are no ISO or EN standards which deal with the sampling of groundwater for PFAS.

Read MoreSpot measurement v. continuous environmental monitoring

August 25, 2023Environmental monitoring has developed considerably over the years. From the time when a consultant went out monthly or quarterly with a dip tape to monitor the groundwater level in a borehole, wind forward...

Read MoreMeasuring Nitrates (NO3, NO3-N) in the field

June 20, 2023The interest in Nitrates is nothing new. One way or another we have been measuring them for half a century.

Read MoreVan Walt Environmental Equipment

A small selection of our environmental equipment